Igor Hiriak, unique soldier from Chernobyl response team: Did anyone go around catching stray dogs in the zone? I don't know. One lived in our camp. We shared food with it.

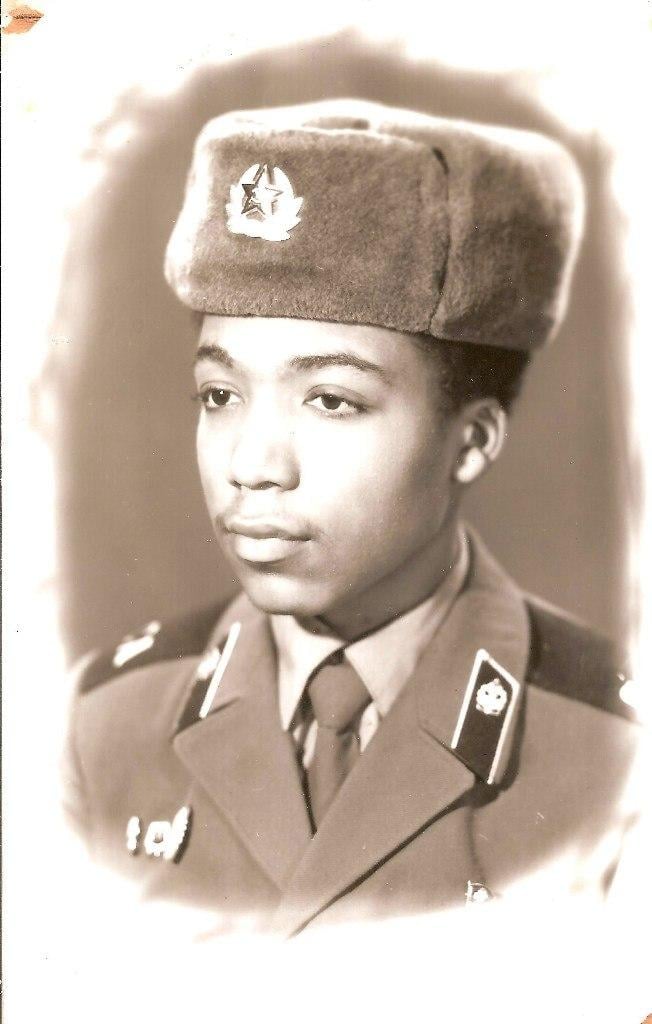

After watching the "Chernobyl" series, many in Ukraine did not agree with the author's reading of those events. People said many things were made up. Meanwhile, one British scriptwriter criticized the authors for not having any PoC actors. People on social networks immediately mocked this remark, because most believed it was unlikely that any soldiers of color ever served in the Soviet forces. However, the ridicule proved to be wrong as there actually was one soldier of another race on the response team! UNIAN was able to find this man.

The best-selling Chernobyl series attracted world attention to people who, at the cost of their health and lives, worked hard to minimize the Chernobyl fallout in 1986. UNIAN talked with a unique participant in those events, Igor Hiriak, the only liquidator of color, a former draft soldier of the Kyiv-based pontoon engineering regiment who was deployed to the Zone.

Why didn't the authors of the best-selling Chernobyl series give any roles to actors of color? That's how the moviemakers were criticized by a British scriptwriter and actress Karla Marie. Her criticism of the series sparked ridicule on social networks. However, it appeared that, at least, one liquidator of color was part of the Chernobyl response team.

In 1986, Igor Hiriak was serving in the pontoon engineering regiment in Kyiv, which was deployed to the Chernobyl zone.

Igor was born in Kharkiv and considers himself a Ukrainian, although he has lived all his life in Russia's Cherepovets. His father remained in Ukraine, but the two barely communicate – the last time Igor visited his homeland was more than 30 years ago.

We met at the train station in Cherepovets, spending the whole day together. We did an interview, a tour of the city, and had a long off record conversation at a dinner. Igor is reluctant to comment on today's current relations between Ukraine and Russia, speaks up for world peace, but then adds that it is the responsibility of all citizens to defend their country.

Igor is already over 50, he is a Chernobyl "veteran." But he looks much younger and radiates tremendous charm and energy. Igor works at a local metallurgical plant, and also does occasional standup shows, sometimes plays extras in movies, and even participates in the reconstruction of the battles of 1812 on the side of the French forces.

After the release of the Chernobyl series, Igor Hiriak became a local celebrity. He has already given about a dozen of interviews and even starred in a talk show in Moscow.

The UNIAN correspondent was the first among Ukrainian journalists to personally thank him for his contribution to the elimination of the consequences of the Chernobyl NPP accident. We talked about life, the accident, and the Chernobyl series, and found out the details that could interest some scriptwriters.

For example, Igor said that in their unit, there was always not enough food – everything was provided to them according to regular norms, but their stomachs needed more, so they would go hunting and fishing right in the fallout zone. Food quality control routine was simple: they would gut the fish they caught, put a dosimeter in it, and if the figures were lower than those of the air, the fish was considered edible.

Igor, tell us about yourself.

My mother is from Cherepovets, but I was born in Kharkiv. When a question arose what nationality should be recorded in my passport, Russian or Ukrainian, I decided that I would choose my nationality on my father's line. Now sometimes people tell me that I am "not Russian". Indeed, I'm not! My father lives in Kharkiv, and I would like to wish him good health and long life. I often think about him, although I haven't seen him for a long time. The last time was in 1970s when he came to Cherepovets. Now we do not even exchange calls.

How did you get to Chernobyl? What tasks did you perform there? How did your comrades-in-arms treat you?

I got to Chernobyl while I was on draft military service. I was drafted in the fall of 1985, right from Cherepovets. I was sent to a pontoon engineering regiment in Kyiv. Following the accident, our unit was deployed to Chernobyl.

The task of the regiment in peacetime is to provide assistance to civilians and victims of natural disasters or accidents. Therefore, our primary task was to arrange a crossing on the Pripyat River. There were two of them. The first one was right at the river station in Chernobyl – to evacuate the population from the territory of Belarus. Another bridge was on the bypass technical canal. Subsequently, we maintained the technical condition of the bridge and the roads leading to it. We also performed random tasks at the station and in the town. We did not get on the roof of the reactor. We did do some work at the train station and the helipad.

When we worked at the station, we would take showers at the spot, changed clothes and disposed of the used uniform.

Did you know in advance what you would do in the accident zone?

When we went there, no one knew where we were going. It was announced that we were going for a drill, that the enemy used nuclear weapons, and that it was necessary to use chemical defense gear. When they arrived, everything gradually cleared up. Later, we were told that there had been an accident at the nuclear power plant and that we must just do what we're told. I do not exactly remember how orders were formulated.

You were then 19 years old. Did you realize the degree of risk and understand how dangerous everything was?

I studied well at school, and I was interested in physics and geometry, and also ROTC. I knew it was dangerous there. In addition, our commanders explained what we must and must not do. And if they said we shouldn't be going somewhere, then it was better not to do it. Dosimeters were constantly used, including in our regiment, and heavily affected spots were marked so that no one would go there.

Were you scared?

I don't know. Were you scared of anything when you were 19? We had to do our job. Those were the times when if they told us something had to be done, it meant it had to be done. I don't know how it would be done today, but it seems to me that it would be the same.

In 1980s, a black guy wearing a military uniform in the Soviet army was not quite a standard situation. How did others treat you?

Since my childhood years, I have always been the best guy in the squad. I've never felt obstructed. People reach out to me, and since childhood years, I have been surrounded by friends. I quickly made friends in the army. When I would go out on a leave to the city, civilians thought that I was Cuban. At that time there were many Cuban military in Kyiv. Commanders would even send me to take our guys from military police. While policemen were trying to figure out what's going on, whether I was Cuban or not, we were already on our way to the base. After all, they were unlikely to try to check whether a "Cuban's" uniform was in line with Soviet statutes...

Have you encountered discrimination based on ethnic or racial grounds?

Sometimes it happened. Strangers would sometimes say: "Get out of here, go home." Some situations were even worse.

Did anyone try to pick fights with you?

Some did. Before the army, and in the army too, I was into sports. At the same time, I looked younger than my actual age... Already at home, after I completed my service, young guys, maybe 14-15-year-olds, tried to pick fights, thinking I was their age. It was always funny when it turned out I was 22.

I haven't had any unpleasant situations for maybe 15 years already.

Are people in your town aware that you've become a celebrity?

In Cherepovets I had at least three thousand acquaintances, but after the release of the Chernobyl series, strangers come up and say they know that I am a participant in the Chernobyl response efforts.

Many people think that I have become famous, but I don’t think so. I didn't do anything to this end. Recently I was in Moscow, people approached me, saying that they had learned about my story from the internet. Now this wave is already passing, but after the first report appeared on Picabu, in, like, 20 minutes, strangers started writing me, asking whether it was fake new or not. First I responded, but the number of messages was getting greater. A minute later there were 80, then 200 ... I thought that I would not have time to read them, and got off the internet. Then reporters called with similar questions.

Did you watch the Chernobyl show?

I did. But when it started, I confused it with another series about this disaster. Then it turned out that we were talking about different things, and I watched the first two episodes. At first it seemed to me that there were a lot of actual facts there, but after I watched it all and attended a panel show, it turned out that some facts were distorted.

The first impression is that there's 80% truth. And after talking with people who also were at the station at the time of the accident, I tend to think that there's 60-70% truth there.

What struck you most? What was fiction?

For example, catching marauders. It wasn't like that. Too much alcohol in the series, too. As far as I know, drinking was unacceptable among conscripts. Throughout the time in the disaster zone, there were only two cases where alcohol was involved. This one time a civilian truck driver scratched my truck. That guy told me they were drinking alcohol to get radionuclides out. There was another case where the soldier drank but he was immediately punished. Among civilians, to my knowledge, drinking was also unacceptable. If some civilians drank, it was probably somewhere where no one could see.

Was order maintained there?

Of course. It was actually martial law. Any misbehavior was curbed.

Okay, there were no free boxes of vodka, but what else in the series w an obvious fiction?

For example, the episode where the miners were talking with the minister. At that time, it was impossible for ordinary workers to slap the minister on the shoulder like that. Also, they showed that the minister had guards armed with automatic rifles. It wasn't the case either. We were deployed in the area, we did have our weapons, but they were locked in a special storage tent.

Did anyone go around catching stray dogs?

I don't know, one lived in our camp. Our guys would go to do their work, and that stray dog sort of stuck around – we would share food with it. I haven't seen anyone shooting stray pets.

Did you live in tents as shown in the series?

Yes, we had two camps. One was on the river shore, near the bridge, and the other one in the 18-kilometer zone, in the forest. We had real tent camps. At first we lived at the shorefront in car cabins and boats, then we moved to the tents, and closer to 1987, trailers appeared.

How much time did you spend there?

I spent there a little more than 2.5 months non-stop. Then I was transferred to a motorized platoon. I would drive the commander around, and then I would also drive him to the bridge to organize the work there.

Have you met someone who became the prototypes for the heroes of the series, Shcherbyna or Legasov?

No, I haven't, but while serving there I once met a Marshal of the Soviet Union. It was in Pripyat, on the bridge. Our service was organized as follows: a week in the forest camp and a week on the bridge. From the forest camp, soldiers were deployed to work at the station, while on the bridge, respectively, they were engaged in maintaining its technical condition. In our "Lenin room" we had a portrait of the Minister of Defense, and they demanded that we know his face. Where is the Minister of Defense, and where am I, a private?! That day, we were preparing the bridge for drawing to allow navigation of vessels when then the UAZ offroader stopped, a man came out wearing a field uniform, without epaulets. However, his pants had wide general stripes. When I approached, another man got out of the car and told me that I was facing a general. I reported according to the protocol. The general asked what we were doing and asked not to draw the bridge until they returned. From 12:00 to 13:00 every day we would draw the bridge. Then he asked where I was from, we talked about Cherepovets – we have a military academy here. And then, I see, our lieutenant running across the bridge, then twenty meters from us, he started marching as a Kremlin cadet, and, approaching us, he reported: "Comrade Marshal of the Soviet Union..." I was so surprised then. I believe he was the marshal of the engineering forces, Sergey Aganov.

Did those two and a half months in Chernobyl affect your health?

Health is definitely didn't get better, but I could say for sure if I could live another life without Chernobyl.

Did you have individual dosimeters?

We were given dosimeters in the form of pens, which were mounted on our pockets, but this device, at most, showed one roentgen, and some had the indicator frozen. We even did an experiment: we once wrapped this dosimeter in a mitten, which was strongly exposed, but as a result we saw the same one roentgen. After that, no one used them. Perhaps this device simply was not designed for "dirty radiation", and it was made for the conditions of a nuclear explosion.

In 1987, "tablet" dosimeters appeared, which did show this. But we had it this way: the order was given that those who received 25 roentgen were supposed to be sent back to the base. But the number of soldiers was limited, so they would write that we received 0.1 or 0.2 roentgen per day. According to those "calculations" some accumulated even as much as 30 roentgen, and only then were they recalled.

What was the fate of those other people on your team with whom you served on that bridge?

Many have passed away. But it is difficult to say why they died. It was never proven that it was a result of their exposure to radiation. After returning home, many liquidators gave up on themselves, started drinking, and this way made things even worse for their already poor health.

How are Chernobyl response operatives supported in Russia?

Immediately after the accident, there were much more benefits, then the situation changed. I think that the opinion of the liquidators both in Ukraine and Russia is the same: the authorities do not provide sufficient assistance. Often people are left alone facing their problems. They are only remembered on Memorial Day, April 26. There is an opportunity to get an early retirement, there is an additional vacation time, to get various vouchers for vacation trips, but I rarely use that. It is easier for me to do this at my job. I work for Severstal enterprise, which provides for us.

In Russia, many commentators have branded this series almost a blasphemy targeting today's authorities. What do you think about this?

They revealed the attitude of the government of those times. Perhaps the series actually has won acclaim precisely due to these scandalous shortcomings. However, this is a feature, so its creators wanted to sell it as successfully as they could. If there's no drama, there will be no disputes and discussions. That's what attracts audiences. Anyway, I'm grateful to them for once again reminding people about those who took part in response efforts following that terrible accident.

I think that in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, many officials feared to lose their jobs and that's why it went down this way. Perhaps, the authorities were concerned that panic might ensue and half of the population would prefer to flee the country. It would take to walk their shoes to understand whether their actions were justified or not. It's always easier to say "I would have done it differently", however, when people get their chance to act, many hesitate.

Would you like to go back and see the Chernobyl nuclear power plant after all these years? The place is booming with tourists today…

I definitely would. I already thought about going there before, and now I also am considering this even more so. I don't think I have the actual opportunity to visit though. It's both about money and time. Probably, this trip will just remain my dream.

Roman Tsymbaliuk