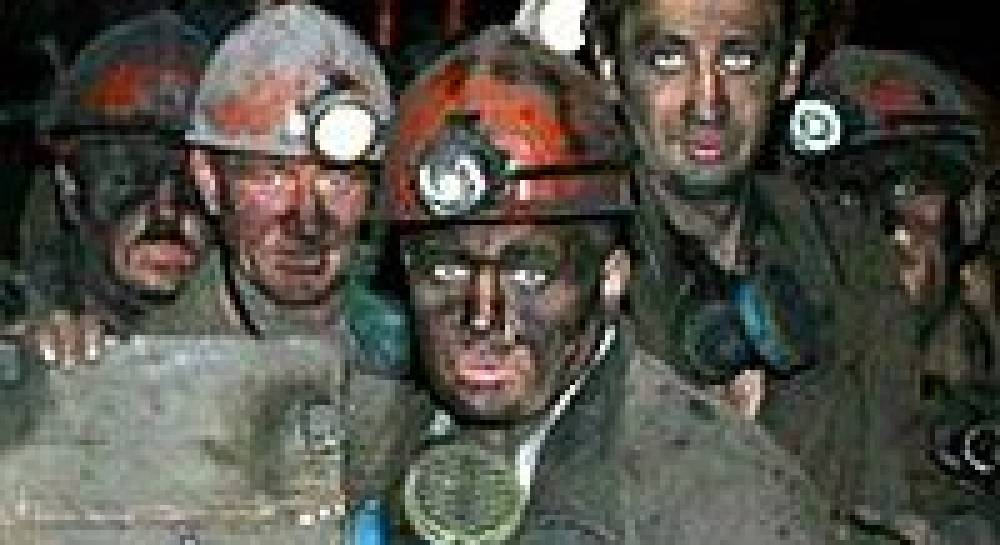

Dicing with danger in Ukraine mines

The BBC`s Gabriel Gatehouse sees at first hand the alarming conditions that make Ukraine`s coalmines some of the most dangerous in the world...

It is a rusty old lift that takes the miners down the shaft at the Ukraina coalmine in the eastern Donbass region.

The shaft is wet, and the whining of the lift cables is accompanied by the sound of rushing water.

Once they get to the bottom, hundreds of metres below ground, the miners have to trudge along dark, damp tunnels, sometimes for kilometres, before they get to the coalface.

Like hundreds of thousands of miners, Dmitry spends his days wedged into a cramped space, hacking the coal from the seam and then shovelling it onto conveyor belts.

He says he has seen worse, and that he is used to the conditions. But he admits that safety is a worry.

And he is right to be worried. Ukrainian mines have an appalling safety record - the second worst in the world, after China.

Thousands have lost their lives in the nearly 20 years since independence. This year`s toll is just over 150, and that is low compared to previous years.

Sparks fly

And down in the Ukraina mine it is not hard to see why it is so dangerous: the tunnels are old and badly maintained. In places the supports holding up the roof have completely rusted through.

It is also pretty hot, and the air is full of highly combustible coal dust. On top of that, at these depths the miners are vulnerable to pockets of methane gas.

And yet, running all along the entire network of tunnels, there is a live electric cable, totally exposed, that powers a cart that transports the coal. As the cart trundles by, sparks fly off the cable overhead.

In July 2002 an accident at this coalmine killed 35 miners, when an old conveyor belt caught fire.

Lydia`s husband was one of the men who lost his life that day. He was 67 years old and had been working down the coalmines all his adult life - for nearly half a century.

Lydia blames antiquated, outdated equipment for his death.

"They don`t give them the money on time," she says.

"The conveyor belts are old. The motors are ancient. It all needs replacing. But that costs money. And where are they going to get the money from when the mine itself is on the rocks?"

The management says that the deaths were the result of human error. But Nikolai Sus, the mine`s deputy director, admits that money is a problem.

"We receive state support. Thanks to that we`re able to pay salaries on time. Without state aid, this mine does not make a profit."

Pride

The Ukraina mine is not an exception. Most state-run coalmines in Ukraine run at a loss. So why not close the mines down?

First of all, the mines provide jobs. The Ukraina mine employs nearly 2,000 people - about one in six of the town`s total population.

Add to that the related industries: bus-drivers who ferry the miners to and from the shaft; shopkeepers who sell the miners their bottles of beer after a long shift.

Almost everyone in Ukrainsk relies in some way or other on the Ukraina mine for employment.

It is a pattern repeated across the industrial Donbass region. No wonder, then, that the citizens of Ukraine`s mining towns take pride in their jobs.

Natalia Tkacheva runs a museum dedicated to the Ukraina mine. In it, there are photographs of old, Soviet-era workers who have acquired legendary status.

Also, there is a shrine to those who have lost their lives here: well over 100 since the mine opened in 1963.

Closing the mines would mean redundancy for hundreds of thousands of workers. Not to mention electoral suicide for any politician in the industrial east of the country.

Ukraine is already facing harsher economic times, as the global financial crisis begins to bite. Many miners here took out loans during the years of economic growth and cheap credit. Without jobs, they would not be able to make the payments.

Distant dream

For some, though, the mines are more than just an unprofitable source of employment.

Chief engineer Aleksandr Marinich believes that coal could reduce Ukraine`s energy dependence on neighbouring Russia. Ukraine, he reasons, does not have Russia`s oil and gas wealth. But it does have coal.

"Why," he asks rhetorically, "should I wait for Vladimir Putin to turn off his gas supply in the New Year? We have billions of tons of [coal] reserves. Our main aim is energy independence."

It is a nice idea. But despite its vast reserves, Ukraine is in fact a net importer of coal.

Its deep and antiquated mines are simply unable to extract enough at a competitive price. With plenty of investment, that could change. And so could safety conditions. But as the financial crisis deepens, a large injection of cash into the mining industry looks like a distant prospect