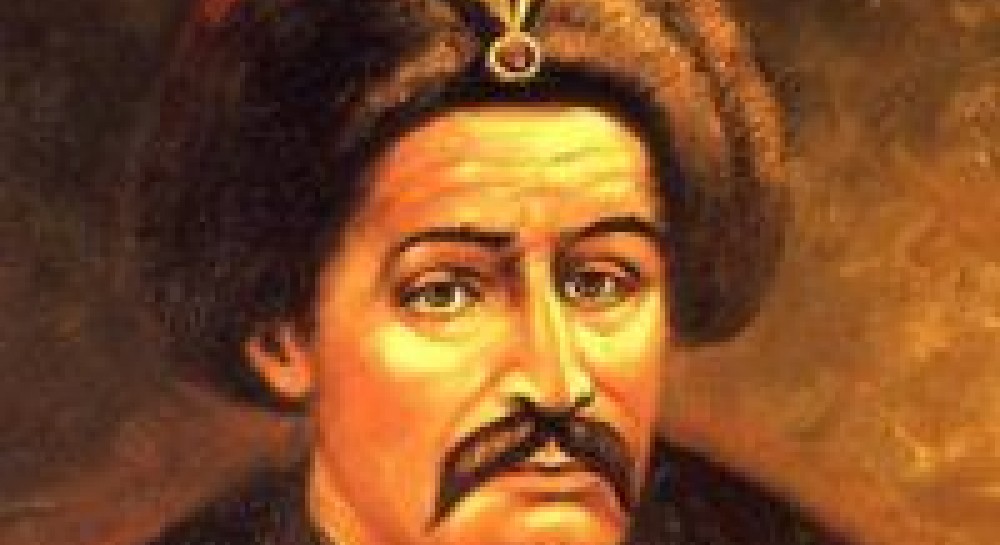

Living book on Hetman Mazepa

Hetman Ivan Mazepa, Ukraine’s national hero, is better known in Europe... Poems about Mazepa were written by Byron, Daniel Defoe, Victor Hugo, Bertolt Brecht... All his thoughts were about Ukraine, its future, and its prosperity...

This may raise a few eyebrows, but it is true: Hetman Ivan Mazepa was the protagonist of one of 17 “oral documentary books” that, for over 23 years, was part of the repertoire of the Kyiv State Historical Portrait Theater.

Ihor Shvedov, a Russian writer and theatrical figure, created these productions from the standpoint of a writer, researcher of history, and director. This theater guided the audience through the well-known and half-forgotten pages in the life stories of its characters. The theater was known far beyond Ukraine: it toured Moscow, many republics of the former USSR, Poland, Germany, Mongolia, and Afghanistan.

In the spring of 1994, in Baturyn, the audience, which included prominent Ukrainians from all over the world who had come to participate in a scholarly conference, gave a long round of applause to Shvedov after his one-actor play Mazepa.

Oleksandr Bystrushkin, People’s Artist of Ukraine, says: “We still do not fully comprehend the significance of Shvedov’s theater. It belongs, no doubt, to history, but it will be a wise book for all theater lovers.” I fully subscribe to this view, for we are talking here about unique synthesis of intellectual work, literary drama art, and scenic skills — all manifested for many years by Honored Artist of Ukraine Shvedov, who was a laureate of all-Union artistic competitions.

Mazepa is a big production consisting of two parts, i.e., two plays — “Favorite of Fortune” and “Hetman.” These include episodes delivered in Russian, Ukrainian, and Polish because Shvedov strove to “preserve the charm of the originals for the audience.” The most important and, in his opinion, most telling pieces were supplied with a Russian translation. The play Mazepa ran in 1991–2001 until Shvedov’s death. It was presented hundreds of times, each time drawing wild applause.

In his book on Shvedov Teatr istorii i propagandy (The Theater of History and Propaganda), the art critic Ihor Mamchur writes that Shvedov often referred to his one-actor plays, which were essentially monologs, as “‘literary-musical productions,’ implying that music had to be an important component of their meaning, imagery, and structure.” In his plays, piano music provides a sensitive, enriching accompaniment to the words and thoughts, helping to depict various situations, sometimes concluding the message or serving as a bridge that links episodes. Here is one example.

Early into Shvedov’s reflections on Hetman Mazepa, Natalka Shevchuk, the co-author of the score and the accompanist, plays a tender Ukrainian folk song, followed by an impetuous and formidable piano melody. Shvedov invites the audience to listen hard — it was a famous, although rarely performed, piece by Franz Liszt, one of his virtuoso tudes. Liszt called them “transcendental,” i.e., surpassing the abilities of a virtuoso pianist. Shevchuk plays ?tude No. 4 called “Mazepa.”

A complete version of Shevchuk’s documentary on Mazepa, committed to paper, was part of the 228-page-long memorial edition Tri ukrainskikh portreta: Mazepa. Vertinskii. Kondratiuk. (Three Ukrainian Portraits: Mazepa. Vertynsky. Kondratiuk), which was supported by the Kyiv City Administration, published by the Tyraz publishers in 2002, and dedicated to first anniversary of Shevchuk’s death. This is a good book indeed. It treats the reader to wondrous revelations on Mazepa. We will relate here a few episodes sufficient to help the reader understand why Mazepa, one of Ukraine’s distinguished sons, is so appealing.

WHEN WAS THE FUTURE HETMAN BORN?

This seemingly simple question caused chaos. Shvedov shows that historians and writers mentioned the following years of Mazepa’s birth: 1644, 1640, 1639, 1632, 1629, and 1626. As you can see, these cover the span of nearly two decades. Shedov was inclined to trust “the writer Valerii Shevchuk, an unquestionable authority in the sphere of knowledge, who based his estimate on the testimony of Pylyp Orlyk: the most likely year of Mazepa’s birth is 1639.” This is confirmed by the authoritative Encyclopedia of Ukrainian Studies. This view is upheld also by Ihor Siundiukov, a historian and journalist, who is well-known to the readers of The Day.

MAZEPA’S IMAGE IN EUROPEAN CULTURE

Shvedov portrays Mazepa in a few convincing strokes. Here is an excerpt from his oral documentary book: “Ivan Mazepa, who has been cursed for centuries in his fatherland, occupies, as it turns out, a very conspicuous place in European literature and art. European classical writers and composers seem to have perceived his image as belonging to the same group as the immortal characters of Prometheus, Faust, and Don Juan.

“This is no exaggeration.

“Look, poems about Mazepa were written by George Noel Gordon Byron, a rebellious English lord (poem Mazeppa), Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe and poem Mazepa, Victor Hugo (Notre-Dame de Paris, Les Mis rables, and Mazepa), the German Bertolt Brecht (Mother Courage and Her Children, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Life of Galileo, and Mazepa), the Russians Aleksandr Pushkin (Poltava) and Kondraty Ryleyev (Voynarovsky), and the Ukrainian poet Volodymyr Sosiura, who penned his poem Mazepa in the Stalin era.

“There is more.

“Juliusz Slowacki’s play Mazepa and Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s opera Mazepa won worldwide recognition. Fundamental research on Mazepa was carried out by the most prominent historians — Sergey Solovyov, Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Voltaire, and others.

“Mazepa, Mazepa, Mazepa…

“What can you say — classical European music has 67 large pieces on Mazepa. The composers are, apart from Liszt and Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Dargomyzhsky, Wagner, etc. What names! The finest brains of their time! Were they all wrong? Were they all doing something that did not really deserve attention?” (pp. 6–7).

MAZEPA HAD NO EQUAL IN TERMS OF TITLES

Here is a brief excerpt from the historical portrait of Mazepa, this time about his recognition in Russia: “He had absolutely everything to satisfy his proudest, insatiable self-esteem. When it was chilly outside, he would make public appearance wearing a luxurious green velvet jacket lined with sable fur and with diamond-ornamented buttons — everyone knew that this was Tsar Peter I’s gift. He was a general of the Russian army, a Full Privy Councilor, and the holder of the highest orders of the time, which lifted him above all Russian generals. He was awarded the title “Prince of the Holy Roman Empire.” All of this is, in my opinion, weighty evidence of the respect Hetman Mazepa enjoyed in Russia at the time.

HETMAN’S STUNNING INTELLECTUAL LEVEL

Shedov offers the following supporting evidence to this statement: “While Tsar Peter I had a hard time finding in Moscow a translator from Latin (who turned out to be a graduate of Kyiv Mohyla Academy) and Prince Aleksandr Menshikov, the second most important figure in the empire, failed to master the skill of writing (instead of a shameful scrawl he thought it better to leave a fingerprint on papers), Hetman Mazepa demonstrated an excellent command of Latin; this was the language he spoke t te- -t te with King Charles).

“The hetman had a fluent command of spoken and written Ukrainian, Polish, Russian, German, and Italian. He did not need an interpreter during negotiations with Turks and Tatars, for he spoke these languages fluently. He tactfully apologized before a French diplomat for his less-than-perfect command of French, while the diplomat reported to his king that he saw right there, on the hetman’s writing table, recent newspapers from Paris and Holland, which the owner had evidently just finished reading” (p. 21). This leads to the following conclusion: human capacity needs to be developed, which the hetman succeeded in doing.

WHY DID MAZEPA SWITCH OVER TO THE SWEDISH SIDE?

It is didactic to know the past, but we need to strive to learn from the past the things that are not always offered to the curious by everyone. Here is what Shvedov writes in his book in this connection: “What exactly happened nearly three centuries ago in the land where we live? Hetman Mazepa, the Ruler of Little Russia, as he was called by Tsar Peter I, decided to choose a different patron for Ukraine, who would be more complaisant and easier to deal with. (At the time politics was perceived precisely in this way: one could survive only under the protection of someone’s powerful wing.) So Mazepa, the generally acknowledged head of the state, changed his foreign policy line, to apply the modern term. This was normal diplomatic practice. The hetman’s act itself — changing his country’s foreign policy — does not imply the smallest of sins, if you look at it without prejudice. This is how it was, is, and will be. Alliances between countries are forged, ruined, and revived again. Some people like these changes, while some don’t. And this, too, is normal.

“From Mazepa’s point of view, it was about creating a free, independent Ukrainian state in the center of Europe. This was out of the question under Tsar Peter I, as the hetman had become learned after many years of interacting with him. Initially, there was the purely military alliance treaty of Pereiaslav. But Muscovy immediately started treating Ukraine as an inalienable part of the empire and ruled here as a superior entity.

“King Charles, on the contrary, offered all the necessary affirmations to the effect that he understood and sympathized with Ukraine’s aspirations for state sovereignty, saying he was ready to facilitate this, without an intention of enforcing the Swedish order here in Ukraine. The hetman lent a hopeful and trusting ear to these words, which were, no doubt, in harmony with the centuries-old interests of the Ukrainian people.

“All his thoughts were about Ukraine, its future, and its prosperity. Here is the explanation Mazepa offered to the Ukrainian Cossacks at the moment he switched over to the Swedes: “Not for my own personal benefit, but for the good of our Fatherland Ukraine and the entire Zaporozhian Army did I accept the assistance of the Swedish king.”

Interestingly, this motive was fully understandable to Peter I’s closest aide, Menshikov. He, of course, zealously fulfilled the tsar’s will, destroying Mazepa followers with unprecedented cruelty. However, this is what he said of the hetman himself and his decision to side with the Swedes, according to the historian Solovyov: “He did this not for his own person but for the sake of entire Ukraine” (pp. 24–26).

Unfortunately, Mazepa could not avoid a major conflict with Russia with its severe consequences. In what follows I will leave a lengthy excerpt from Shvedov’s book on Mazepa’s act without comments. Let me just mention one essential feature: the cited text has been taken from a book by a Russian writer, who argues that we should not believe what has been imposed on us as the only possible truth.

TSAR PETER I’S SPECIAL EDICT

It turns out that in those distant times the need to cancel the anathema on Mazepa was the topic of serious discussions on numerous occasions, because the curse had no religious grounds and was dictated by Tsar Peter I’s personal anger. Here is a little-known fact found in Shvedov’s book: “Tsar Peter I was generally reluctant to review his decisions. But after he calmed down and cooled off a little, he issued a decree, six months after Mazepa’s death, officially ordering Great Russians to refrain from rebuking Ukrainians with Mazepa’s name and his treason. After Tsar Peter I’s death they did everything to bury [this] in the archives” (p. 69).

VIEW MAZEPA WITH PRIDE, NOT CONDEMNATION

Some are likely to disagree with this statement. However, this would be pointless. What characterized Mazepa’s activities was this slightly modified description offered by the Crimean philosopher Pavlo Taranov — “an absence of inflexibility: it is as much distanced from straightforwardness as motion is from square wheels.” Shvedov reflects on this aspect in his documentary on Mazepa: “Some disliked, and some do now, the methods Mazepa used. A respectable Kyiv newspaper cited a no less respectable author as saying about Hetman Mazepa: ‘He was a complex, inconsistent, cunning, and often insincere figure; just think about how dubious, to put it mildly, were his choices of benefactors — Doroshenko, Samoilovych, etc.’

It seems that there is nothing that can be said to rebut this statement. However, is this situation unique? Is it characteristic of Mazepa alone? In our day and age the methods used in politics are no better. Benefactors change, and no one remains true to his or her convictions, ideas, and course in life forever.

Look around: aren’t we too presumptuous in slandering the great dead? Isn’t it wiser to take a closer look at their lives and see the causes and effects? This is something to be learned from this.” (p. 44) George Billing said it right: “Experience adds to our wisdom, but does not take away from our foolishness.”

There are many revelations awaiting the reader once he chooses to familiarize himself with Mazepa’s historical portrait. There was nothing unnatural or affected in what came from the stage. The author gradually recreated in his imagination the distant image of the hetman, the faces of those who surrounded him, his contemporaries, while peering into, reflecting on, and trying to comprehend the causal connections between actions, events, and phenomena. Shvedov’s play was an equally great relish for the ear, heart, and mind. The people in the audience, as I had a chance to observe, had the happy feeling of experiencing the events themselves. So the effect Shvedov aimed for was reached.

I consider Shedov’s method of creating historical images his valuable discovery. He noted: “My works most likely follow the laws of portrait painting. Some features are brought to the foreground, some remain in the shade, while certain details, which for some appear to be most important, are left out altogether. I have developed the main criterion: only the pieces that the audience likes are acknowledged completed. If the people in a capacity audience follow the play with glowing eyes, as if they were playing a movie in their imagination, and then applaud, thank, and discuss it — nothing can be more precious than this.”

Shvedov was proud of the success of his Mazepa documentary, for it facilitates historical memory. He loved what the German writer Jean Paul said: “Memory is the only paradise from which we cannot be expelled.” US President John Kennedy once said that “a nation reveals itself not only in people whom it gives life, but also in those whom it honors and remembers.” This thought is very true.

It is hard to disagree with the proposal of Prof. Volodymyr Panchenko, Vice President of Kyiv Mohyla Academy, that educational efforts have to play an important part in this cause. In particular, he suggested republishing popular books on Mazepa, like the one Valerii Shevchuk once wrote for the Veselka Publishers. In my opinion, this series should include Shvedov’s documentary on Mazepa — hopefully, it will indeed.

By Yurii Kylymnyk, a Candidate of Sciences degree in Philosophy