Since the British government accused Russia of an “illegal use of force” against the United Kingdom by attempting to poison former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in the English city of Salisbury, Twitter has become a battleground.

Supporters and defenders of the Russian government have clashed over who was to blame, and which side to believe; politicians and diplomats have joined in on both sides, @DFRLab reports.

Much of this invective appears organic, driven by angry users who are convinced that their cause is right; such storms are a regrettable part of everyday life online. Some incidents, however, appear to involve organized activity, including possibly fake accounts masquerading as English users, in the well-known pattern of the “troll factory” in St. Petersburg.

On March 17, when an apparently British user called @Rachael_Swindon posted an online poll asking whether the British government’s evidence was adequate to blame Russia. The poll returned a hefty majority in favor of “No.”

POLL:

— Rachael (@Rachael_Swindon) March 17, 2018

Are you satisfied that Theresa May has supplied enough evidence for us to be able to confidently point the finger of blame towards Russia?

Please vote and share for widest possible range of opinions.

The account which posted the poll is a vocal supporter of the UK’s Labour Party, a critic of the ruling Conservatives, and has a substantial following. The fact that the poll received over 15,000 votes, mostly anti-government, was therefore not, in itself, remarkable.

What was remarkable was the origin of its amplifiers. Many of its most recent retweets — and, it is legitimate to assume, votes — came from accounts which are either Russian-language, or systematically post pro-Kremlin content.

This appeared to be an attempt by pro-Russian users to influence the online poll, and thus to create the appearance of greater hostility towards the UK government than UK users themselves showed.

To assess the extent to which Russian or pro-Kremlin accounts helped amplify the tweet, @DFRLab conducted a machine scan of its spread through multiple stages of retweeting, using the Sysomos online tool.

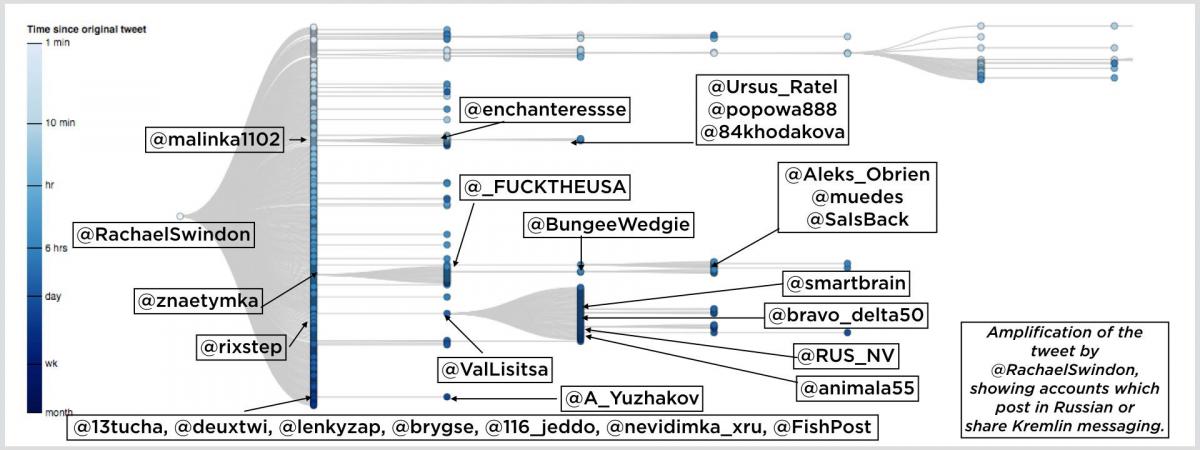

Spread of the @Rachael_Swindon tweet. The original post is marked on the left; each subsequent point indicates a Twitter account, and each column, traveling right, indicates a retweet, or retweet of a retweet. The vertical axis shows elapsed time, with the first retweets at the top. (Source: Twitter / Sysomos / DFRLab.)

The scan showed that the early traffic (top half of the image) was generated by UK-centric accounts, but that the later traffic (bottom half) was substantially driven by Russian-language and pro-Kremlin networks, going through multiple retweet iterations as the message spread.

Analyzing the profiles involved in a massive amplification effort, the experts underline that they have previously spread messages favorable to Moscow, on various topics. That's including posting direct attacks on researchers, including the Bellingcat team of investigative journalists, and on those who provide evidence of apparent crimes committed by Russia and its allies, attacking White Helmets and the broader West.

Read alsoU.S. sanctions Russian "troll factory", 19 individuals for election meddlingNone of these Russian accounts have an organic focus on, or interest in, UK politics; their content is dominated by pro-Kremlin messaging, mostly in Russian or English. Their purpose in retweeting the poll therefore seems to have been to spread it to a Russian audience which could be expected to vote against the UK government.

This intervention was small in itself, impacting one poll, from one account. However, the source account was an influential member of a politically vocal UK community; thus, by targeting it, the Russian accounts may have hoped to reinforce their message among UK opposition supporters.

The poll did not reflect the “mood of the British people.” It reflected some British sentiment, and a significant injection from pro-Kremlin and Russian-language accounts. Thus, the author of the poll appeared to have been taken in by one of the accounts which spread it most widely to a Russian constituency.